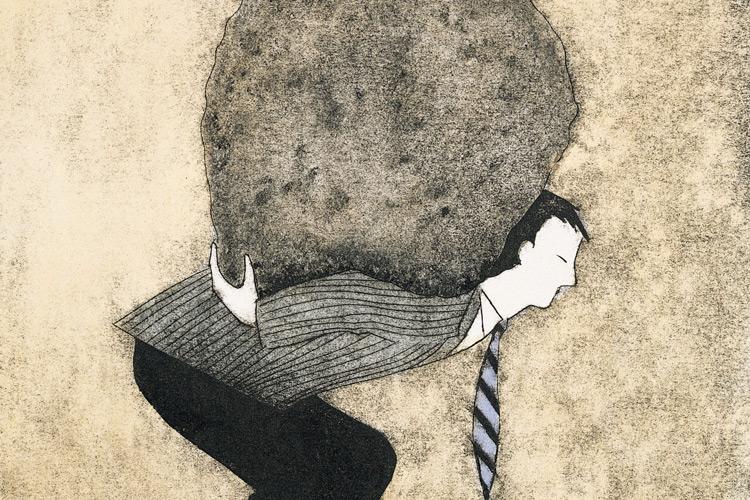

According to the safety watchdog the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) stress is “the adverse reaction people have to excessive pressure or other types of demands placed on them”.

It also makes clear that stress is different from pressure. While pressure can be a motivator, prolonged stress becomes a risk to health and safety.

Work stress can lead to mental and physical ill-health including depression, anxiety and depression. It can also increase the likelihood of accidents at work as people are more likely to make mistakes when they are stressed.

One of the most innovative unions addressing this issue, Prospect, has been campaigning under “Stress, Stigma and Solutions”. It recognises that when dealing with stress you also need to tackle the stigma – otherwise the size of the problem won’t be known and you will not get a proper solution and therefore will not have a positive impact. Prospect is active in encouraging solutions to make a difference to individuals’ and their organisations’. See www.prospect.org.uk/stress.

Signs of stress

The HSE says that stress can show itself in many different ways. It advises managers to look for changes in the way people behave that could be linked with excessive pressures at work. The following short-term and long-term symptoms can all be signs of work stress and something you also, as an individual, should be aware of:

- Changed moods, anxiety, depression, negative thoughts and disturbed sleep patterns.

- Changes in heart rate, increased blood pressure, “palpitations” and hypertension (high blood pressure).

- Sweating, reddening, blushing, eczema and psoriasis.

- Muscle stiffness and soreness.

- “Butterflies” in the stomach, dry mouth and appetite suppression.

- Increased susceptibility to some infectious diseases.

Stress, your rights and the law

The Health and Safety at Work Act requires employers to protect the health, safety and welfare of their employees and this includes taking reasonable steps to prevent or control the risks of work-related stress. The TUC says that stress is a hazard covered by the Health and Safety at Work Act in the same way as any other hazard, such as a hazardous substance or an unguarded piece of machinery.

Case law has established that employers must protect the mental as well as physical welfare of their employees. The first case to test this in the courts was Walker v Northumberland County Council [1995] IRLR 3. It confirmed that as part of the employer’s general duty of care to provide a safe workplace, they must also take reasonable steps to avoid exposing employees to a health-endangering workload.

In addition, under the Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations, employers must carry out a risk assessment. This should assess the risks to the mental as well as physical health of their employees. Where the risk assessment finds that there are significant risks of exposure to stress, they must take measures to manage those risks.

Managing work-related stress – the Management Standards

HSE developed guidance that integrates an understanding of stress into normal management practices – called the Management Standards; they refer to 6 organisational factors that, if met, promote health. These are:

- Control – how much say people have in the way they carry out their work.

- Support – the encouragement and resources the employer, line managers and colleagues provide.

- Relationships – good practice includes promoting positive working to avoid conflict and having in place effective measures to deal with unacceptable behaviour (such as bullying which is a major cause of work stress).

- Role – being clear about employees’ roles and avoiding conflicting roles.

- Change – effectively managing and communicating organisational change.

Prospect fully supports these but is campaigning for a 7th factor. Under Prospect’s “Good Work” campaign it encourages organisational fairness because the evidence shows fair companies are healthier.

Stress management techniques

Be wary of stress management approaches that individualizes stress. Where organisations’ focus on resilience, this is acceptable provided it includes organisational resilience. The TUC, quite rightly, warns against a resilience approach solely focussing on workers.

What should be included in a good stress policy?

A far better approach to managing stress is to have an effective policy that is put into practice. The TUC advises that a good stress policy should:

- Recognise that stress is a health and safety issue and is about the organisation of work.

- Be developed jointly and agreed with trade unions and have commitment from the very top of the organisation.

- Be based on a fair blame-free approach and apply to everyone.

It should:

- Prevent work stress by identifying its causes and eliminating them, where possible.

- Recognise and deal with stress-related problems through consultation, participation and cooperation.

- Ensure that managers, supervisors and employees are trained and recognise to deal with and prevent work-related stress.

- Include the rehabilitation of employees suffering stress and independent confidential counselling.

- Contain agreed arrangements for joint monitoring and review to assess the effectiveness of the policy.

An example of a stress policy can be found on the HSE website.

For more information to address stress, listen to Prospect’s podcast “Looking after your own work stress”.